By Ann Carol Ulrich

You

see them on the highways, any time of the year, picking at the

dead animals that got in the way of cars. Nature's morticians?

In a way. They are the black-billed magpies (Pica pica),

probably the most common, most conspicuous bird found in this

region.

You

see them on the highways, any time of the year, picking at the

dead animals that got in the way of cars. Nature's morticians?

In a way. They are the black-billed magpies (Pica pica),

probably the most common, most conspicuous bird found in this

region.

Magpies are members of the crow family (Corvidae), which comprises not only crows, but ravens and jays as well as the Clark's nutcracker. This family of perching birds has the reputation of being noisy and raucous, courageous and aggressive, and intelligent. Their stout, sharp-pointed bills are tough and powerful, enabling these birds to eat practically anything... and they do.

Measuring from 17 1/2 inches to 22 inches, black-billed magpies are large birds with a long streaming tail and white wing patches. They walk in short, jerky steps. They are not much good at rapid flight. The iridescent green tail is actually longer than the bird's body and often gets in the way of the bird's attempt at flight when there is a strong enough wind.

The birds are native to Eurasia as well as America, where we find them in the western United States and along the western coast of Canada. Magpies need open stretches for foraging along the ground. The range of the black-bill does not overlap with that of the yellow-billed magpie, which is found in southern California.

In Colorado we find the black-bills in open country near heavy brush or occasional trees. They wander erratically in winter.

Their call is an ascending whine or a rapid series of loud harsh notes, often heard as "mag, mag, mag!" Some have been kept as pets and can imitate the human voice quite well.

Like other corvids, they are curious and adaptable to man's environment. Around where I live, I often see a congregation of magpies at the garbage bin, having a good old time.

Cattlemen in these parts will complain what a nuisance black-billed magpies are. After all, they have been despised as thieves and scavengers for decades. Magpies attack weak or injured stock, keeping open wounds from branding scars from healing by picking at the sores.

Magpies have also been known to kill young poultry and rob hens' eggs. They feed their young with the eggs and young of swallows, it is known.

Yet, mapgies have their good side, too. Everyone knows they clean up the roads by eating carrion. They also pick the ticks off the backs of larger animals, such as deer. Magpies also devour those harmful grasshoppers and rodents that threaten our crops.

As do other members of the Corvidae family, magpies mate for life. Their nests are elaborately built, intricate affairs, built in trees or thorny bushes. The nests are several feet deep and completely domed over.

In a study done in 1968, an ornithologist found that it took 40 days for a pair of magpies to build the huge stick-basket of a nest. Probably for this reason magpies use the same nest year after year.

Those nests that are abandoned are used for shelter in inclement weather by other birds and sometimes for breeding purposes in the spring. The magpie nests have two entrances. The birds line a mud cup with rootlets, then surround it with a wall of sticks.

The twiggy dome that is built over the top is used to fend off hawks. The female lays from six to nine greenish-gray eggs which are heavily speckled with brown blotches.

People may refer to the magpie as a pest, but being a native Easterner I had never seen one until four years ago. I still take that second glance in awe at what is perhaps a little clumsy and overbearing, but nevertheless a beautiful creature with its iridescent green and graceful tail. The magpie, to me, will always be a symbol of the West.

Robins return to announce arrival of spring

By Ann Carol Ulrich

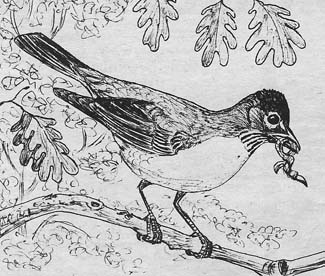

You

know spring is right around the corner when you see your first

robin. I spotted mine a couple weeks ago, about the middle of

February. He was a fat little orange ball of feathers, sitting

in a tree with a flock of red-winged blackbirds which had

apparently stopped in the area for a breather on their

migration route. the robin seemed a bit stymied, intimidated

by the snow. But the fact that he was there made me wonder --

can spring be far behind?

You

know spring is right around the corner when you see your first

robin. I spotted mine a couple weeks ago, about the middle of

February. He was a fat little orange ball of feathers, sitting

in a tree with a flock of red-winged blackbirds which had

apparently stopped in the area for a breather on their

migration route. the robin seemed a bit stymied, intimidated

by the snow. But the fact that he was there made me wonder --

can spring be far behind?

The American robin, Turdus migratorius, is widespread across North America. It measures from 9 to 11 inches, has a black head and tail and a conspicuous orange breast. The female's head is slightly grayer than the male's. Jokingly nicknamed the red-bellied thrush, the robin is a member of the family Turdidae, which includes the thrushes and bluebirds.

The male's melodic song consists of a series of rich caroling notes that rise and fall. His "Merrily, Cheerily, Cheer-up, Cheerily" can be heard as one of the first at dawn and one of the last before the sun sets.

Accustomed to cohabitation with humans, robins can be found in villages, orchards, farm lands, parks and cities, raising their two or three broods a year and nesting in some of the most unlikely spots, be it the crock of a tree or a window sill or a mailbox.

During the courtship season the male battles with other males and afterwards is on constant guard against others of his kind who might encroach on his family's food supply.

The female robin does most of the nest construction, using twigs, grasses and other fibrous materials, then cementing them together with mud. The male does not participate in this homemaking, but stands on watch and may feed his mate on occasion. Four or five greenish-blue eggs are laid and the female sits on them with little or no help from the male. However, he contributes his share of duties by helping to feed the young.

The baby birds are easily recognized in summer because of their spotted breasts. Often seen standing and running along the ground, robins eat worms, insects and fruit. Like many other birds, robins suffer a mortality rate of 80 percent a year.

Occasionally a robin is seen wintering in the northern states. I even recall a couple hearty critters around my home last December. Most likely these are birds which have summered farther north in Canada. They prefer moist woods or fruit-bearing trees in the colder weather, seeking out cedar bogs and swamps, and may not be noticed by the casual observer.

Unlike the other thrushes that migrate at night, robins and bluebirds migrate in flocks during the day. And now that March is here, and spring right around the corner, we will no doubt see the arrival of many more migratory species that breed in this valley.

Bird's Eye View

By Ann Carol Ulrich

It

is April. The tourists are scattering and the snowcats are

going into hibernation. One animal that is coming out of

"hibernation" is that unforgettable but handsome creature, the

skunk. His incomparable odor is evidence of his increasing

presence as the snow melts and he leaves his winter habitat.

It

is April. The tourists are scattering and the snowcats are

going into hibernation. One animal that is coming out of

"hibernation" is that unforgettable but handsome creature, the

skunk. His incomparable odor is evidence of his increasing

presence as the snow melts and he leaves his winter habitat.

Actually, the skunk does not hibernate as some other mammals do in winter. When food is scarce and temperatures drop, certain animals experience varying degrees of dormancy. Bears crawl into dens and sleep, but can be roused, thus displaying partial dormancy. Ground squirrels exhibit complete dormancy in which their body temperatures actually lower, putting the animal into a state of torpor.

The skunk, on the other hand, may settle down in a den and sleep for long periods of time, particularly those skunks found in northern ranges and here in the mountains. To escape the bitter cold skunks seek out refuges anywhere they can -- under buildings, underground, under large piles of brush. It's not unusual for someone to discover a skunk wintering beneath their woodpile, for example. They sleep much of the time in winter, but may venture out now and again on a warmer day.

There are four species of skunks found in the United States. The one we are most likely to see is the striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), which ranges from southern Canada throughout most of the United States to northern Mexico. Just about everyone is familiar with the bold pattern of black and white that makes this carnivore (meat eater) conspicuous to all, warding off any would-be predators.

Another species we might run across is the spotted skunk, which is smaller and has a pattern of white stripes and spots. Striped skunks are more common. They measure about 30 inches in length, including an 8 to 10 inch tail. In fall striped skunks weigh about 10 pounds after gorging themselves with insects, leaves, grain, nuts and carrion. In spring you can expect them to weigh half as much as they did before the snow fell.

Belonging to the mammalian family Mustelidae, skunks are related to weasels, martens and wolverines. These are all relatively small creatures with well-developed perianal scent glands. The skunk, by the way, is obviously the most highly developed Mustelid with this characteristic.

Striped skunks have adapted well to the presence of man, whom they do not fear. They often live near houses and thrive in areas where land has been broken up into small woods and fields. Farmers' fields seem to be an ideal habitat. The skunks feed on the mice and other small mammals that are displaced by plowing.

Skunks also feed on nesting birds and their eggs. In late summer they find beetles, crickets, grasshoppers and caterpillars to delight their palates. They have been known to raid chicken houses and have frequented caves to eat the occasional bat that drops down.

Breeding usually takes place in late fall or early spring. Kits are usually born in May with four to ten the usual size of the litter. Blind and hairless, the kit weighs an ounce at birth. The black and white pattern shows plainly on the kit's skin. After three weeks the eyes open and the mother skunk weans her babies after six or seven weeks, at which time she may take them along on hunting excursions.

By autumn the family breaks up and by the time young skunks are one year old they have reached maturity. Their life span is 10 to 12 years. Since they are nocturnal animals, skunks do not show themselves much during the day.

Skunks are slow and short-legged. Ten miles per hour is about the best they can do when running hard. They cannot climb trees. Despite the fact that they'd make an easy catch, skunks have few predators. Most animals have been conditioned to turn away from those blazing black and white stripes. Only the great-horned owl preys regularly on skunks. It doesn't seem to be at all bothered by the musky, putrid odor. These owls often have the noticeable scent on them.

Rather tame animals, skunks do not spray unless attacked or disturbed. Even then it will try to give a warning to its attacker by lowering its head, erecting its tail, and stamping its front paws. Then if this fails to scare off the intruder, the skunk turns its back on its enemy and squirts an amber-colored fluid from its anal glands, called methyl mercaptan. This musk which skunks emit is very strong and unpleasant, lingering in the air for a long time -- often for several days.

They are extremely accurate shots from 10 to 12 feet away. If the spray gets into the intruder's eyes, it burns and causes a temporary blindness but will not damage the eyes permanently. The spotted skunk actually stands on its head when it discharges its weapon.

Many skunks die on our highways every year. They treat approaching cars as intruders, having never learned to run away. Skunks have made good pets in the past. They can be tamed quite easily. But I don't recommend petting your neighborhood skunk. He'd probably let you because he is a gentle-natured creature and only sprays when he absolutely has to. But most wild animals are protected and it is illegal to capture and keep them as pets. Besides, you can't rule out the possibility of them being rabies carriers. Let's enjoy the little stinkers from a distance... a long distance.

The solitary kingfisher can be seen along rivers

By Ann Carol Ulrich

While

driving along Highway 82, where the river runs parallel to

Emma's Curve, you might see him any time of the year. A

top-heavy, short-legged creature with a crest, perched on a

telephone wire, patiently watching the rushing waters below.

He is searching for a fin snaking its way just beneath the

river's surface.

While

driving along Highway 82, where the river runs parallel to

Emma's Curve, you might see him any time of the year. A

top-heavy, short-legged creature with a crest, perched on a

telephone wire, patiently watching the rushing waters below.

He is searching for a fin snaking its way just beneath the

river's surface.

He is the belted kingfisher, Megaceryle alcyon, a large, grayish-blue bird that inhabits the banks of rivers and lakes, feeding on fish by diving headlong from the air. Measuring from 11 to 14 1/2 inches, his very long and heavy fish-catching bill is what makes the kingfisher appear top-heavy.

The bird is named for the mythological daughter of Aeolus, Alcyone, whose husband perished in a shipwreck. Alcyone was so grieved at the death of her lover that she threw herself into the sea. The gods took such pity on her that they transformed Alcyone and her husband into kingfishers so they could roam the water side by side. During periods while they nested on the open sea, the waves calmed and no storms unsettled the sea. Today these are referred to as "halcyon days."

Six of the 87 species of kingfishers live in the Western hemisphere. Only two of these six breed north of the Rio Grande -- the green, and the belted kingfisher, the belted being the most common.

Seen singly or in pairs along rivers and ponds, Megaceryle alcyon is usually a solitary dweller, jealously patrolling his fishing grounds with his loud, dry, rattling call. The harsh grating sound he gives has been compared to the clicking of a fisherman's reel. The courtship call is more of a mewing.

On sighting a fish, the kingfisher flies from its post and hovers over the water before it plunges in after its prey. Although kingfishers usually select small fingerlings to feed on, they can snag a fish as large as themselves. The bird swallows it whole, and an inch or two may stick out from its bill until the quick-acting digestive juices take care of the rest.

Unlike most species of birds, the female kingfisher is the more colorfully marked throughout the year. She resembles the male with her large head, heavy bill, crest, and bluish-gray markings. She has the white underparts and the blueish-gray breast band, but she displays a rufous band beneath this which the male does not have.

No nest is constructed. Instead, the mated birds burrow a long tunnel into the side of river bank or cliff. They dig 3 to 15 feet with the corridor being either straight or crooked. Swallows have occasionally shared the same tunnel.

The parents share in incubating the 5 to 8 white eggs. This takes 23 to 24 days. Regurgitated fish bones build up under the clutch by the time the eggs hatch.

The mother bird is too short-legged to stand over the blind and naked babies, who must cling to one another in a ball to keep warm. By two weeks their pin feathers appear, and in another two weeks they are able to fly, and shortly leave home after their fishing lessons.

This aquatic bird can actually walk underwater

By Ann Carol Ulrich

What

is small and gray, looks like a wren, bobs like a sandpiper,

and dives under water? The answer: a rather remarkable

creature common to our area all year round which is

sometimes known as the Water Ouzel. Its common name is the

Dipper (Cinclus mexicanus) and it is only one of four

species of birds that comprises the family Cinclidae.

The dipper is the only perching bird in North America that

is totally aquatic. It inhabits western highlands to

altitudes of 12,000 feet, and always lives near rushing

water.

What

is small and gray, looks like a wren, bobs like a sandpiper,

and dives under water? The answer: a rather remarkable

creature common to our area all year round which is

sometimes known as the Water Ouzel. Its common name is the

Dipper (Cinclus mexicanus) and it is only one of four

species of birds that comprises the family Cinclidae.

The dipper is the only perching bird in North America that

is totally aquatic. It inhabits western highlands to

altitudes of 12,000 feet, and always lives near rushing

water.

My first encounter with this slate-colored, solitary bird and its entertaining antics was about five years ago while enjoying a quiet picnic lunch on the bank of the Roaring Fork next to the Rio Grande Trail in Aspen. The bird immediately caught my attention with its constant bobbing motion, which gave it another nickname, the "teeter bird." Its strong yellow legs and feet enable the dipper to "fly" underwater, propelling itself with its stubby, rounded wings. In shallow water it appears to "water ski" over the surface, hunting for insects.

When it goes underwater in search of snails, fly larvae, and fish fry, movable flaps or scales close over the bird's nostrils. The dipper also possesses an enlarged preen gland for water-proofing its feathers. A warm undercoating of down lies beneath the outer plumage. The dipper actually walks on the bottom of streams in addition to its diving and swimming. It may remain submerged as long as half a minute, then pop up out of the water some 20 feet downstream.

Its call is a sharp "zeet," and the song is wren-like and bubbly, full of clear, sweet trills, and is not limited to springtime. Rather than migrate, the dipper moves to lower altitudes where it can find plenty of running water.

Females and males look alike while the juvenile birds have spotted breasts. The female builds a huge nest with an arched entrance at the side. Sometimes the nest is hidden behind a waterfall, consisting of a globular weave of moss and grass. Two broods may be raised a year. Three to six white eggs hatch after 16 days, and then the young are on their own after 15 to 24 days.

The eery common nighthawk

By Ann Carol Ulrich

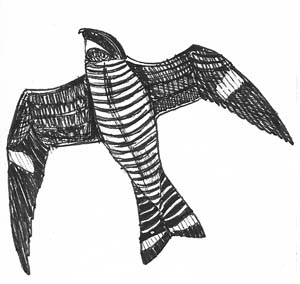

Aerial

dives at dusk, ending in a loud vibrating buzz, are

characteristic of one peculiar bird in our area. Such is the

courtship display of the Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor).

Aerial

dives at dusk, ending in a loud vibrating buzz, are

characteristic of one peculiar bird in our area. Such is the

courtship display of the Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor).

Not a hawk at all, the nighthawk belongs to the order Caprimulgiformes and a family of nocturnal insect eaters called the Goatsuckers. He and his cousins are told by their large flat heads, small bills, enormous mouths, and distinctive white patches on wings or tail. The nighthawk's eyes are merely a slit during the day, but at night they become startlingly huge, round, and black.

Pioneers mistook the birds as hawks because of their swift flight and hawk shape. Measuring 8 1/2 to 10 inches, the nighthawk is about robin-sized. He has a long notched tail and long pointed wings with a broad white wing bar. His brownish-black mottled back and tummy help the bird to blend in with the forest floor.

They can be found in open woodlands, fields, and clearings, and they like towns where there are roosting trees or fence posts. The birds often nest on flat rooftops, where they lay only two eggs. Nighthawks are widespread in North America except for the low deserts of the Southwest, and tundra. In winter they migrate to the subtropics of Mexico and South America.

Although the birds fly during the day as well as at night, they are most commonly seen at dusk. Their call is a unique "beert" or "peent" (much like the woodcock's). They sit lengthwise on tree limbs or diagonally on wires, a characteristic of other goatsuckers, or nightjars, as they are also called.

Others in the goatsucker family include the whippoorwill of the East, Chuck Will's Widow of the South, and the lesser nighthawk of the Southwest. The poorwill of the West is the only other nightjar likely to be seen in our region.

The name "goatsucker" is an old term that goes back about 2,000 years. Its derivation seems to be shrouded in mystery. Legend has it that this family of birds, which has been held in superstitious awe, was feared and believed to take milk from the udders of goats.

Of course, there is no evidence to support this rumor. Yet, I always found it curious in H.P. Lovecraft's short story, "The Dunwich Horror," how whippoorwills were used to invoke that quality of eeriness that set the mood for the tale.